By Jessie Oliver

Jessie Oliver is a member of ACSA and sits on the ACSA management committee. She is also a PhD student at the Queensland University of Technology, in Brisbane Australia. She attended the Citizen Science Association Conference in May of 2017 with the assistance of a Shuttleworth Foundation Flash Grant.

Reflections by Jessie Oliver (@JessieLOliver via twitter):

In early 2017, I had the good fortune of meeting Alasdair Davies when he ventured to Brisbane Australia, where we both participated in a workshop about technology use for conservation. My role at the workshop was to share my knowledge of how scientists and members of the public, or citizen scientists, were working collaboratively to make innovative discoveries that have benefitted conservation efforts. While there, I shared information regarding local, national, and global efforts aiming to increase capacity, uptake, and outcomes of citizen science, technology use, and conservation actions. I absolutely had my heart set on attending the Citizen Science Association Conference in 2017 that was set to take place in Saint Paul Minnesota, but I wasn’t sure I would be able to given the substantial funding required to get to the U.S. from Australia.

Why did I want to go so far away? I wanted to run an accepted symposium that would explore how citizen science varies in different regions of the world. I hoped to discuss with a panel of citizen science leaders, how scientific practices, cultural, societal, and political factors are shaping the spread, uptake, and diversification of citizen science in four key regions of the world. I also hoped to attend so that I could meet people with expertise in Human Computer Interaction (HCI) technology design strategies, environmental acoustics, and citizen science. Doing so also had the potential to further my own research, investigating how to design engaging citizen science technology to review environmental acoustic recordings, which I also wanted to present as a poster.

You can imagine my surprise when, several weeks later, I received an email informing me that I had been chosen by Alasdair to be awarded a Shuttleworth Foundation Flash Grant! Being afforded such an amazing opportunity, I quickly got to work organising a fireside-chat style symposium with the following panellists:

- Myself, Jessie Oliver, a Management Committee member of Australian Citizen Science Association, sharing knowledge of Australian citizen science, which was largely acquired through my four years of volunteer work helping to develop the Association;

- Darlene Cavalier, CEO of SciStarter, summarising citizen science projects across the United States based data from the project finder;

- Muki Haklay, co-director of Extreme Citizen Science (ExCiteS), discussing his experiences from a European point-of-view;

- Elizabeth Tyson, a former global fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, sharing extensive knowledge of citizen science in China, which she also discussed in THIS podcast, and

- Austin Mast, speaking to how people can work collaboratively to digitize biological museum collections through the Worldwide Engagement for Digitizing Biocollections (WeDigBio).

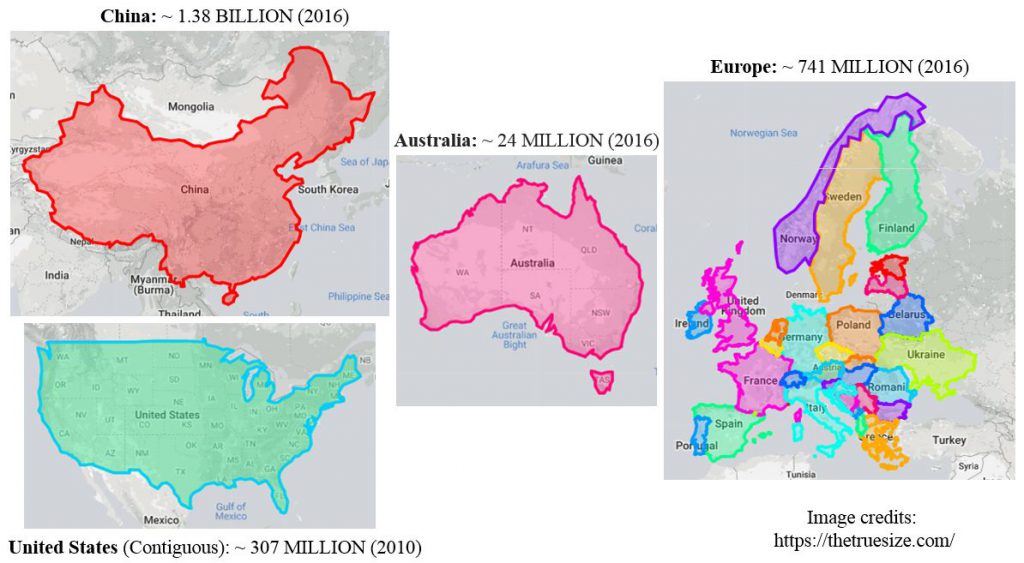

This symposium highlighted key differences between citizen science regionally and what factors drive this variation. Language is certainly a key factor for how project information and resources are disseminated across Europe, having to contend with far more languages than Australia, China, and the United States. While all these regions are relatively similar in geographic size, the distribution and overall populations are vastly different. Australia, for instance, has vast expanses with relatively few people, and a population of only about 24 million primarily concentrated in five cities. At the time of the conference, the U.S., Europe, and Australia all had formed young citizen science associations working to facilitate networking between citizen scientists, scientists, and other stakeholders. China, by contrast, had several projects across the nation, but had yet to establish a network to actively bring stakeholders of different projects together, although this is now underway. Environmental and biodiversity-focused sciences were shown to dominate citizen science relative to other sciences for all regions featured.

WeDigBio is an example of how increases in technological infrastructure now allow people from a variety of regions to also contribute to global projects both in person and online. Access to these technologies, however, varied by region. In the latter half of the symposium, ample time was allocated for audience questions and discussion, and this proved incredibly useful, allowing for inclusion of perspectives from regions such as Japan, Iran, Iraq, New Zealand and South America. This exchange of information led to a greater appreciation for the need to carefully identify and understand what factors are likely to influence the regional development of citizen science.

There was an amazing amount of networking and learning to be had as well. In terms of my own technology design research, I was absolutely thrilled to meet and discuss my research with people such as Jenny Preece, who research citizen science and HCI technology design! These discussions later inspired me to organise a workshop at the #OzCHI2017 Conference in Brisbane, which brought citizen scientists and scientists together with designers to explore technology development needs for saving species like glossy black cockatoos, koalas, wombats, and shorebirds! I was also delighted to find that my #CitSci2017 poster exploring how to design engaging technologies for citizen scientists to review acoustic data, was also well received by former colleagues from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. I met many of the citizen science leaders I had corresponded with remotely while working for the TV series The Crowd & The Crowd. My attendance and work with the show also prompted an invite to a conference meeting regarding a Global Mosquito Alert Consortium, and I subsequently joined the global working group.

Many of the connections and lessons learned from the conference have continued to positively impact my citizen science work in Australia and abroad. This conference was incredibly well run with very interesting, empowering, and informative ways to convey information beyond the standard talk formats. My experiences there directly fed into my work on our organising committee for the last Australian Citizen Science Conference (#CitSciOz18) as well. While in the U.S. I often shared experiences regarding the development and happenings of ACSA, which later led to speaking invitations to share this knowledge at events. Most recently, for example, I spoke remotely from Brisbane at #CitSciNZ2018 Symposium, which was led by Monica Peters in New Zealand.

Relationships I have forged as a result my receiving the Shuttleworth Flash Grant continue to be fruitful. Next, I am planning to travel to Geneva in early June to attend the European Citizen Science Conference (#ECSA2018) and participate in several meetings and workshops before and after the conference as well. One of those meetings is at the UN office in Geneva to discuss the UN Sustainable Development Goals, the potential for citizen science to contribute to these goals globally, and the role that the nascent Citizen Science Global Partnership will play. It’s wonderful to reflect a year later and realize that Shuttleworth Foundation helped to catapult all aspects of my citizen science work to new heights, and I am beyond grateful for this opportunity!